Marxism Won’t Solve Canada’s Rental Housing Crisis – Despite What Ottawa Thinks

By Peter Shawn Taylor, Goodman Report

This article originally appeared in C2C Journal and is reprinted by permission.

C2Cjournal.ca | Ideas That Lead

As the Trabant was to cars, so was the panelki to housing.

The East German-made Trabant, powered by an obsolete two-stroke engine and lacking in all modern conveniences, stands as stark proof of Communism’s inability to respond to market demands, produce high-quality consumer goods or keep up with technological change. The same holds true for Bulgaria’s panelkis, shoddily-constructed government apartment towers made from prefabricated concrete panels that allocated a mere 100 square feet of living space per inhabitant. Massive, soulless structures of this sort once dominated the outskirts of major cities across Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in sprawling complexes.

Andrey Pavlov grew up in Bulgaria’s capital city of Sofia during the Communist era and recalls how the panelkis loomed over the urban landscape like a grim curse. “As with everything built during the Communist years, they were a complete disaster,” says Pavlov, now a finance professor at the Beedie School of Business at Vancouver’s Simon Fraser University, in an interview. “Not only were they depressing to live in, but the execution was terrible – there were gaps between the prefabricated panels and water constantly leaked into the units. Even brand new they were falling apart because there was no incentive to do better.”

Besides the terrible quality and cramped conditions, the allocation of panelkis was even worse, determined by corruption rather than need. The most desirable units – those with a view, or perhaps fewer leaks – went to Communist Party members and their families. “It was especially bad for anyone who was not politically connected. But that’s what you get when the government provides all the housing,” Pavlov warns. “The world has tried such a system many times before and it has failed every time. To see it proposed here again in Canada is very disappointing.”

The proposals Pavlov is referring to come from the office of Canada’s Federal Housing Advocate, a newly created position meant to act as a national watchdog over Canada’s housing sector. Last month Marie-Josée Houle, Canada’s first housing advocate, released a series of little-noticed reports and recommendations that blame Canada’s current housing crisis on private capital, or what she calls the “financialization of housing.” Houle claims her commissioned studies “confirm” the harm done to tenants by the private sector and that this necessitates an official federal investigation and corrective action.

‘It is a document that would make Marx and Lenin proud,’ says Pavlov, having read the Federal Housing Advocate summary report. ‘It is shocking that any government-funded agency could produce such a thing.’

The reports, written by a variety of academics and housing activists, take deliberate aim at firms or investors that “profit from rent increases” – a condition that captures essentially all privately-owned rental housing, since rent increases are a necessary component of any market-based business model. These arguments, along with 51 recommendations, are collected in The Financialization of Housing in Canada: A Summary Report for the Office of the Federal Housing Advocate by University of Waterloo planning professor Martine August. Among the recommendations: regulating banks to prevent them from lending to any profit-making rental firms, prohibiting pension funds from investing in such firms, denying them access to federal mortgage insurance and other government programs, placing a cap how many rental units these firms can buy and expropriating any “affordable” housing units they might already own. Other demands include a call for coast-to-coast, iron-clad rent control, an end to Real Estate Investment Trusts’ (REITs) tax status and the abolition of all federal policies that “privilege home ownership over renting.”

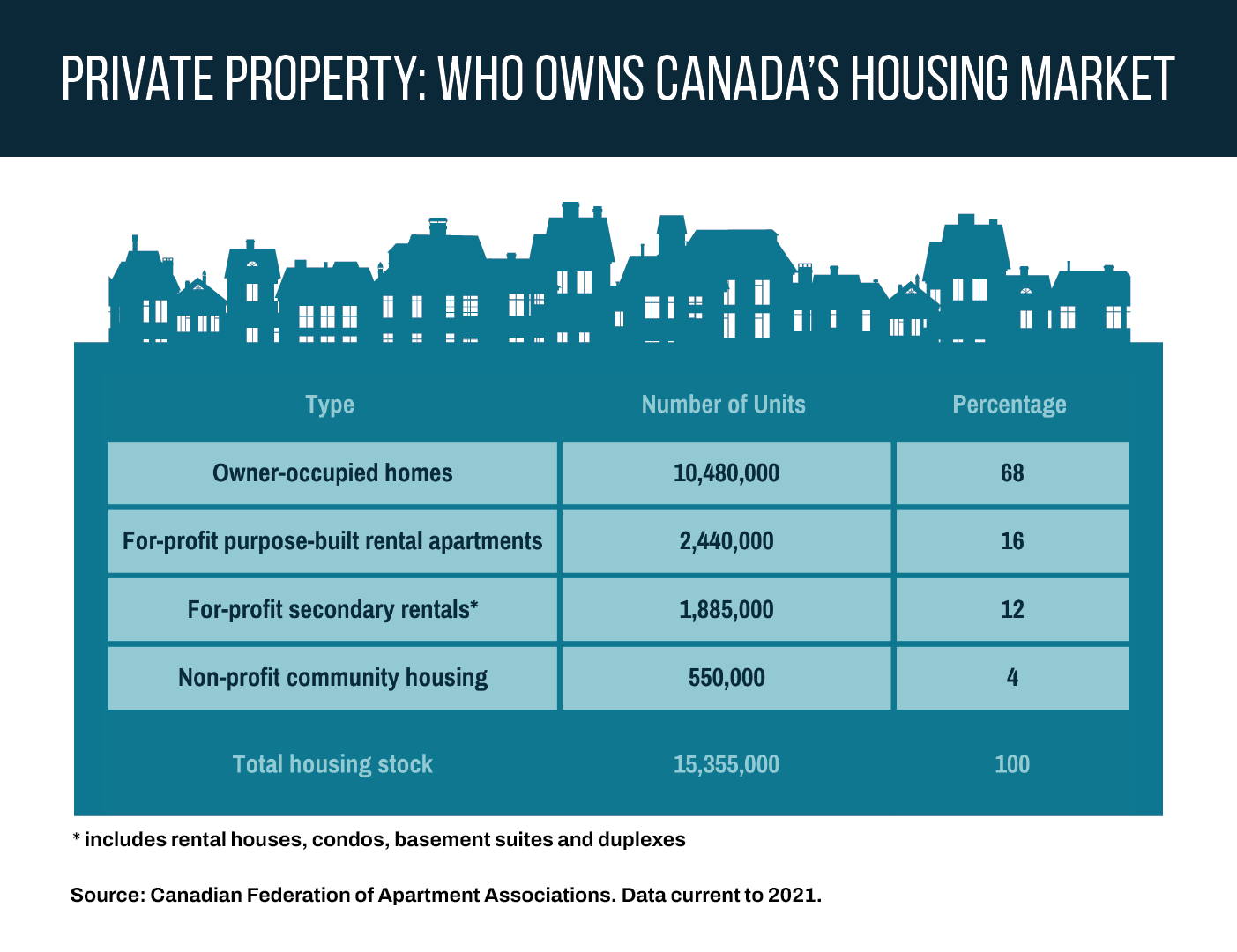

The thrust of most of these recommendations is to make it impossible for profit-seeking private investors to participate in Canada’s rental housing market. With 89 percent of Canada’s approximately 4.8 million rental units already in private hands, such a policy would inevitably push the entire sector towards government ownership or oversight. Rather than fixing Canada’s housing crisis, such an extreme, ideologically-driven effort would result in widespread calamity – making it impossible to add new supply and dooming the existing rental stock to panelki-levels of disrepair.

“It is a document that would make Marx and Lenin proud,” says Pavlov, having read the Federal Housing Advocate summary report. “It is shocking that any government-funded agency could produce such a thing.” And remember, he’s speaking from experience.

Canada’s Nationalized Housing Strategy

In 2017, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government announced a 10-year, $37 billion National Housing Strategy meant to tackle housing affordability. It hasn’t worked. Due to Canada’s inability to build new houses, condominiums and apartments in sufficient volumes to meet rising demand – largely as a result of suffocating government rules and restrictions (see this two-part series by C2C Journal, here and here) – Canada’s housing problems have expanded into a full-blown crisis. Even the recent downturn in house prices, precipitated by the Bank of Canada’s interest rate hikes, hasn’t helped the rental market, as rents continue to climb. In response, the Liberals have doubled down with additional promises to spend over $70 billion by 2027-2028, much of it in an effort to make housing “more affordable” by funding non-profit, community and co-op housing projects.

Often overlooked amid this torrent of cash is the controversial legislation that undergirds the Liberals’ housing strategy. According to the 2019 National Housing Strategy Act, the federal government “recognize[s] that the right to adequate housing is a fundamental human right.” Beyond creating this novel “right” to housing, the Act also birthed a bureaucracy to entrench the concept, including the Federal Housing Advocate and National Housing Council, an advisory body meant to inform the federal housing minister on human rights-related housing matters.

Since the dawn of modern property law, housing – whether owned or rented – has always been a commodity freely negotiated between interested buyers and sellers in an open market. No longer. The Liberals now claim to have discarded this centuries-old practise in favour of a moral imperative. Transacting for rental housing on the basis of free market principles, says Advocate Houle in a press release, means “denying people their fundamental human right to affordable, dignified, and safe housing.” It is a philosophical shift with significant economic consequences.

“Human rights were originally conceived to preserve liberty and hold back the overreach of the state,” observes Queen’s University law professor Bruce Pardy in an interview. “Today they’ve become the means for some people to control the behaviour of other people.” In the case of rental housing, this alleged new right is being interpreted by Houle and other housing activists to mean that private sector landlords should not be allowed to raise rents, evict tenants for non-payment or otherwise operate their property in a way that makes them money. While restrictions of this kind may sound pleasing to current tenants, such policies would make the entire concept of private ownership of rental housing untenable. “The report is essentially saying that the only legitimate way for people to be housed is through state provision,” says Pardy, after reviewing August’s summary report. “I consider that to be full-blown Communism.”

Pardy notes implementation of the various bans, restrictions and expropriations promoted in the Federal Housing Advocate’s list of recommendations are all within the realm of legislative possibility. “Constitutionally, property rights are not listed in the Charter,” he advises. Pardy, however, disputes the notion that the federal government has actually created a true “right” to housing. “All the National Housing Strategy Act does is make a statement of policy,” says Pardy, who is also the executive director of Rights Probe, a new Canadian think-tank focused on law and liberty. “It is not enforceable in law. You can’t go up in front of a judge and insist that the government give you a house because of what it says.” Since this purported new right is not enshrined in Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms either, any subsequent government can simply repeal the legislation and make it disappear instantly.

‘Financialization is contributing to unaffordable rents, worsening conditions, and a rise in evictions,’ says a September press release from Houle’s office.

Regardless, the Trudeau government is currently setting policy on the basis that housing is a human right. And it is to this end that federal-appointee Houle commissioned her research reports declaiming the allegedly toxic role played by private capital in the rental housing market. She has since used her authority to request a formal review by the National Housing Council “on the human rights impacts of corporate investment in rental housing, also known as financialization.”

What is Financialization?

Given Houle and August’s repeated use of the word, it seems necessary to determine what they mean by “financialization.” Both declined several interview requests from C2C Journal to explain their position in more detail. According to Houle’s website, “Financialization is a term used to describe how housing is treated as a commodity – a vehicle for wealth and investment – rather than a human right and a social good for people and communities.” From this perspective, “financialization” appears to refer to how Canada’s housing market used to operate, up until the Liberals declared it to be a human right.

Houle and August use “financialization” as short-hand for their concerns about the recent growth in corporate investment in Canada’s real estate market. Attracted by the prospect of steady returns and (until recently) low interest rates, REITs, pension funds and other large corporate entities have been buying up apartment buildings and other rental properties from smaller operators across Canada since the early 2000s. According to August, the largest 17 financial firms now control 344,000 suites, or 20 percent of the country’s purpose-built rental housing stock. “Financialization is contributing to unaffordable rents, worsening conditions, and a rise in evictions – often due to renovations and rebuilding with the goal of charging higher rents,” says a September press release from Houle’s office. Adds August, “Financialization has been flagged as a driver of social inequality and is associated with the violation of the right to adequate housing.”

To summarize the Federal Housing Advocate’s position: greedy corporate owners are cornering the market on rental properties and using their leverage to push rents up, force low-income tenants out and otherwise discriminate against vulnerable populations. To protect the human rights of tenants, it is thus necessary to banish the owners of capital by whatever means necessary. Such Marxist-style animosity towards the private sector cannot simply be dismissed as the dusty political fixations of an obscure federal bureaucrat and a few dirigiste-minded academics. Rather, the concept that there’s something illegitimate or immoral about profit-minded entrepreneurs participating in the rental market is gaining ground throughout the machinery of Ottawa.

Beyond the upcoming National Housing Council review panel on “financialization” requested by Houle, the Supply and Confidence Agreement between the federal Liberals and NDP similarly commits the Trudeau government to “tackling the financialization of the housing market by the end of 2023.” And the 2022 federal budget also contains the promise of a “federal review of housing as an asset class,” which appears to be synonymous with “financialization.” Whatever it means, it is very much a live issue.

Rage Against Corporate Real Estate

“What we are seeing is a demonization of ‘financialized’ landlords,” says John Dickie, pausing to emphasize the adjective’s polemical nature. Dickie is president of the Canadian Federation of Apartment Associations (CFAA), an industry group that represents the full range of private-sector landlords across the country: from individual investors with one or two rental units up to large “financialized” firms such as REITs with tens of thousands of apartments for rent; CFAA members account for about a third of all privately-owned rental units in Canada. In fact, recent Statistics Canada data suggests that Canada is very much a nation of landlords, with nearly one in every five homeowners having more than one property.

“Running through these reports is the idea that profit is evil,” says Dickie. “But profit is just the return that people get on their investment. Without the prospect of profit, there will be no private investment.” Within the diverse collection of profit-seeking landlords represented by the CFAA, Dickie says there is no reason to believe that larger corporate entities are more likely to raise rents than any other owner, including small “Mom and Pop” landlords. Nor do Houle and August present verifiable evidence to back up their accusations that evolving ownership trends are driving rent inflation. “The people who own apartments have two characteristics,” says Dickie. “They have an inclination to be in the rental housing business. And they want to make money.”

If there is a difference between corporate landlords and smaller operators, says Dickie, it’s that bigger firms are more likely to run their operations in a professional and predictable manner. And this is to the advantage of tenants who appreciate regular maintenance and formalized procedures. As for claims made by one Federal Housing Advocate report that “financialization” harms “members of Black communities, recent immigrants and refugees,” the author again provides no proof to back up this volatile contention. Says Dickie, “Just walk through any rental building and you will see a kaleidoscope of the world in the hallways. It is the private sector that houses ‘racialized’ people.” He also points out that professionally-managed apartments are much more likely to use computerized systems to select new tenants, all-but eliminating the risk of discrimination or bias.

The standard measure for industry concentration is the market share controlled by the five largest firms. In Canada’s heavily-regulated banking sector, that figure is 85 percent, in telecommunications, it’s 87 percent. In the rental housing market, it is less than 5 percent.

REITs, which own about 10 percent of Canada’s rental housing stock, are subject to the most biting criticism from the Federal Housing Advocate’s reports. August suggests REITs enjoy an unfair advantage over other landlords because Ottawa taxes them differently from corporations and individuals, claiming there is “no social justification” for such a policy. But Pavlov, who specializes in real estate finance, points out that as trusts, REITs are required to distribute most of their profits directly to unitholders – who then pay personal taxes on that income. This avoids double taxation of profits at the institutional and individual level. Investors in corporations are provided with a dividend tax credit to achieve the same end. “REITs are not unique at all,” explains Pavlov. “Every other mutual fund works exactly the same way.”

Of greater import is August’s claim that the rental housing market has become worrisomely concentrated due to “financialization,” raising the spectre of anti-competitive behaviour. The 2022 federal budget made a similar allegation. “There is a concern that this concentration of ownership in residential housing can drive up rents,” it stated. Neither August nor the budget provides any proof for this allegation, but it is an easy contention to test. The standard measure for industry concentration is the market share controlled by the five largest firms. In Canada’s heavily-regulated banking sector, that figure is 85 percent. The same goes for telecommunications, with the five largest Canadian phone companies accounting for 87 percent of sales.

In the rental housing market, it is less than 5 percent; the five biggest private sector firms hold just 208,000 out of 4.3 million privately-held units. “This is an industry that is extremely unconcentrated and highly competitive,” Dickie states firmly. In fact, the country’s second-largest landlord is Toronto Community Housing Corp., a city-owned social housing agency.

As for arguments that rental conditions have worsened since the mid-2000s when corporate landlords began entering the marketplace in greater numbers, the facts again belie the claims. In September, Statistics Canada released its latest Canadian Housing Survey. Both of Statscan’s two measures of housing affordability reveal substantial improvement at the lower end of the income scale. The percentage of households spending more than 30 percent of their income on shelter declined from 24.1 percent in 2016 to 20.9 percent in 2021 – a drop of 13 percent. And the share of households in “core housing need,” meaning their accommodations fall below acceptable standards for size, condition and cost, is currently 10.1 percent, a drop of nearly 20 percent since 2016. Despite the upheaval of Covid-19 and the recent run-up in rents, evidence suggests things are getting better, not worse.

The Benefits of Financialization

Regardless of long-term trends, however, no one doubts that Canada faces an immediate housing crisis. And the fundamental reason is an insufficient supply of new units. Rather than trying to rid rental housing of “financialization” says Frank Clayton, senior research fellow at the Centre for Urban Research and Land Development at Metropolitan Toronto University (formerly Ryerson University), he suggests we need a lot more of it. A little history reveals why.

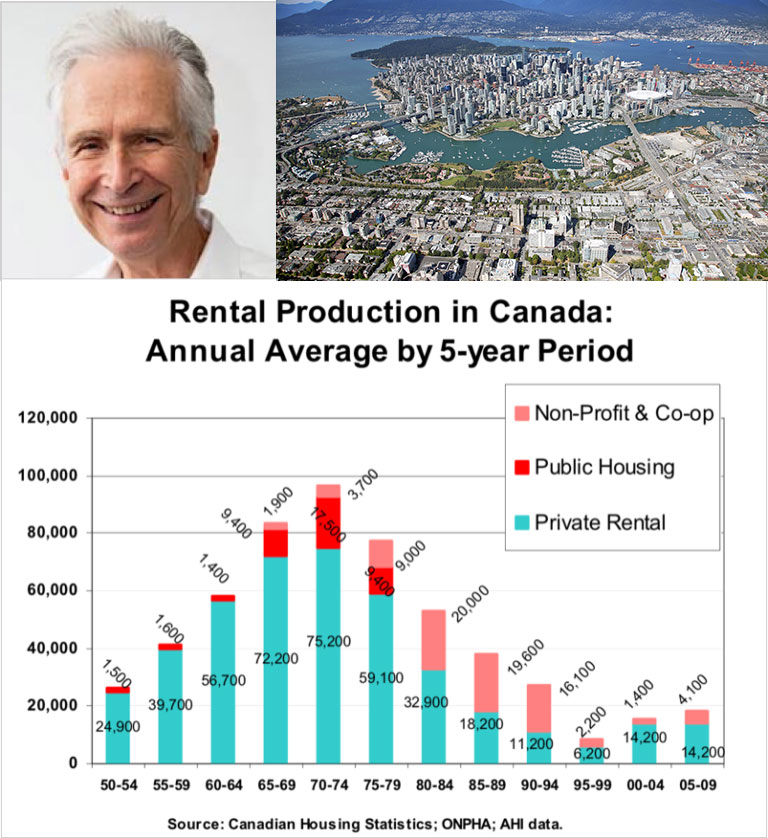

“Back in the 1960s, there was quite a bit of ‘financialization’ in the rental housing market,” notes Clayton, taking issue with the Federal Housing Advocate’s claims that the current situation is unprecedented. Life insurance companies and syndicates of doctors and lawyers were once frequent buyers and builders of apartment buildings because of the reliable income streams they produced. A substantial portion of Canada’s current rental housing stock was built in this era due to the ample flow of private capital. But federal tax changes in the mid-1970s and provincial rent control laws led to an exodus of capital from the sector. “It no longer made sense to build purpose-built rentals,” recalls Clayton.

At the same time, most Canadian households shifted their attention away from renting to buying single-family homes in the suburbs or condos downtown, significantly reducing demand for new apartment buildings. Average annual rental unit construction in Canada by the private sector fell from 75,000 units in 1970-1974 to a mere 6,200 units in 1995-1999. Sporadic government funding for social housing projects was never enough to replace the huge absence of private capital for new apartment blocks.

Only recently have conditions improved sufficiently to lure large institutional investors, such as pension funds and REITs (which were created in 1993), back into the rental market. Driving this return is the recent run-up in housing prices, which has forced many families to give up on their dream of home ownership, plus significantly higher levels of immigration. “Gradually it has started to make more sense to get back into rental housing,” says Clayton. This year purpose-built rental construction in Canada hit an annualized average of 60,000 units. While still below production levels half a century ago, it now eclipses condo production and is fast catching up to single-family homes. But the long absence of private capital means that even with REITs and other corporate investors pouring money into the sector, there’s still a grave shortage of supply. It will take many more years to bring the market back into balance – if the private sector isn’t banished entirely.

In addition to constructing much-needed new units, corporate real estate firms are also putting their own money into improving the buildings they already own. This too has become a matter of great political controversy. “When an owner invests in a building, they are installing new appliances and amenities and updating the structure. They are improving and modernizing the housing stock,” says CFAA president Dickie. “Up until five years ago, this would’ve been considered a good thing. Now these activists are furious that renovations lead to higher rents.”

At issue for the Federal Housing Advocate and other housing activists is that tenants may be forced to leave their apartments during lengthy renovations, a process they pejoratively label as “renoviction.” If “renovicted” tenants cannot to afford the new higher rents in their old building, they will be forced to seek shelter elsewhere. This shifting of lower-income tenants into older, unrenovated buildings as newly-improved buildings attract a clientele that can afford pricier rents is known as “filtering.” Clayton admits that it might be fairer if displaced tenants were given the right to return to their old units at their old rent, at least for a few years. But in general, he considers the modernization process propelled by “financialization” to be a great benefit to Canada as a whole. “If you want to improve the housing stock, you’ve got to spend money on it,” says Clayton. “If the private sector doesn’t re-invest, everything is going to end up looking like public or social housing.” And who wants to live in a Canadian panelki?

Social Housing is no Solution

In their efforts to banish private capital from Canada’s rental housing market via rent control, expropriation and other restrictions on landlords’ ability to charge market-based rents, Houle and August lean heavily on the belief that government is capable of replacing everything done by self-interested capitalists. If the private sector is violating the human rights of tenants by upgrading apartments and raising rents, then collective ownership must be the solution. Yet ample evidence suggests such faith is wildly misplaced, often fatally so. The mere fact that a housing project is operated on a non-profit or community basis is no guarantee that it serves the best interests of its tenants.

Consider Toronto’s Swansea Mews, a 114-unit housing complex owned by Toronto Community Housing that was abruptly closed this summer because its concrete roof collapsed, leaving one tenant hospitalized and approximately 400 displaced. How did the building fall into such a state of disrepair? While housing activists decry landlords’ habit of pouring their own money into the upkeep and enhancement of their buildings, Swansea Mews’ tenants experienced the damage caused by the opposite condition. Many of Toronto Community Housing’s units are falling apart because they haven’t been maintained to safe and proper standards. According to its current budget, the social housing behemoth faces a capital repair backlog of over $1.5 billion.

“The reason social housing like Toronto Community Housing gets run down is because there isn’t the money available for upkeep,” says Clayton. Politicians habitually prefer the excitement of announcing new projects over the mundane obligations of keeping existing operations in good repair. It is a chronic failing of public housing. Consider also New York City Housing Authority, the largest landlord in the United States. It faces a staggering US$25 billion bill to fix numerous problems throughout its 177,000 apartments, many of which have lacked heat and water in recent years. And don’t forget the disastrous Grenfell Tower fire in West London in 2017 that claimed 72 lives; it too was owned by the local public council.

As for the alleged mistreatment of visible minorities by “financialized” landlords, the Federal Housing Advocate’s own report on racialized tenants reveals that Toronto Community Housing is just as likely to remove tenants who don’t pay their rent as are private companies. Simply declaring housing to be a human right does not obviate the inevitable burdens and responsibilities of ownership. A landlord who cannot evict non-paying tenants will not be a landlord for very long. They will soon be the bankrupt owner of a derelict building.

Supply Above All

According to the federal budget, Canada needs to build an additional 3.5 million new homes by 2031 to meet expected demand. As the accompanying chart shows, community and non-profit housing comprise just 4 percent of total homes and 11 percent of Canada’s total rental housing stock. To meet the national need for more housing without the participation of profit-making capitalists would require that the entire non-profit sector expand many times over in just a few years. It is clearly an impossible task, regardless of the socialist fantasies propounded by Canada’s housing activist cadre.

Beyond the non-profit sector’s obvious lack of capacity and expertise in delivering large-scale housing developments, there is the matter of finding the trillions of dollars necessary to put all those shovels in the ground. In the absence of private capital, says Pavlov, it falls to Canadian taxpayers to foot the entire bill. And “there just isn’t enough money in Canada for governments to raise the taxes necessary to replace the private sector in housing,” he says. “Pushing taxes above current levels would kill the economy. It is delusional to think that government could build all the housing we need.”

Shifting blame for the current housing crisis onto the private sector may be useful in diverting attention away from political culpability, but it obscures the fact that only the market can permanently solve a lack of supply.

One rare glimmer of common sense in the Liberal’s flawed “human rights” approach to housing is the Canada Housing Benefit, a new $4 billion program jointly operated with the provinces that provides a monthly cash payment to renters struggling with housing affordability. Personal subsidies of this sort offer a practical solution to the high cost of rent since it allows low-income households access to well-built and maintained market-based units, rather than having to submit to the many indignities of social housing. Relying on the private sector to house poorer Canadians in this way represents a far more efficient use of taxpayers’ dollars than funding expensive but scarce co-op or community housing developments.

Unfortunately, there’s a catch. As Clayton points out, in a time of constrained supply, cash benefits simply fuel higher rents without solving the underlying problem. “Housing vouchers only work when there are vacancies,” he says. And that leaves only one viable solution to resolving Canada’s housing crisis – build as many new houses and apartments as quickly as possible. And the route to greater supply always runs through the private sector.

In the same way that activists and public sector unions have sought to eliminate the profit motive from essential care sectors including childcare, long-term senior care homes and health care on moral grounds, housing activists now seek to seize control of the rental housing industry for the non-profit and public sectors. Yet this collectivist urge fails to understand that if something is in short supply, it is due to interference with market forces. This is why waiting lists and under-provision are habitual problems whenever the public sector exerts a monopoly. Shifting blame for the current housing crisis onto the private sector may be useful in diverting attention away from political culpability, but it obscures the fact that only the market can permanently solve a lack of supply. Where there is unmet demand, profit-seeking entrepreneurs are ideally and uniquely motivated to tackle the problem.

Whatever the Trudeau government and the Federal Housing Advocate may claim about the invented new right to housing, efforts to banish capitalism from rental housing will inevitably leave tenants far worse off by impeding repairs on existing buildings and preventing the creation of new supply. “If you want to do anything about housing, you’ve got to involve the private market in a huge way,” says Clayton. “Investors have both the capital and the expertise to get it done. There is no better mechanism to provide more housing than the market mechanism.”

Peter Shawn Taylor is senior feature editor of C2C Journal. He lives in Waterloo, Ontario.