Change is coming – land use policy updates

Goodman Report

All three levels of government have recently added to the flurry of housing related policy announcements; regrettably, the promise of those policies remains decidedly mixed.

The federal Liberals led off, on April 16, with a budget that left many of our clients feeling underwhelmed or worse. The big headline was an increase to the capital gains tax inclusion rate, from 50% to ~67%. By our math, the change takes an additional 9.8% of gains from the sale of an investment property. This is counterproductive when all levels of government are otherwise urging the private sector to speed the delivery of purpose-built rental properties (i.e. investment properties) to address a severe national shortage. The increased capital gains tax reduces the incentive for investment in new projects and it encourages owners to hold onto land with a low cost base, rather than selling for redevelopment. Lose lose.

Another fail was the $1.5-billion Canada Rental Protection Fund, touted to “preserve and grow our affordable housing supply.” As with the BC Rental Protection Fund, moving existing apartment buildings from private to non-profit ownership does nothing for supply – and it inflates rent costs by taking market units out of the rental universe and forcing the average renter to compete for fewer available apartments. It also locks up properties that would otherwise be ripe for the kind of redevelopment that actually increases the rental housing supply. Perversely – and perhaps on the bright side – the Fund will remain functionally unfunded, limiting its impact. The belatedly released fine print showed that the new program will have only $5 million in the first year and $120 million per year thereafter. For a national program, it’s hard to see how this will have any impact, whatsoever.

Longer term, some of the budget initiatives may be more helpful in addressing the housing shortage: an accelerated capital cost allowance for new purpose-built rental buildings; expansion of CMHC’s Apartment Construction Loan Program (formerly RCFi); and a new Canada Builds program aimed at delivering affordable purpose-built rentals on government, non-profit and community owned lands. Even here, however, the timelines seem badly out of sync with the hardships residents are feeling today.

Vancouver’s Response to Provincial TOA Legislation

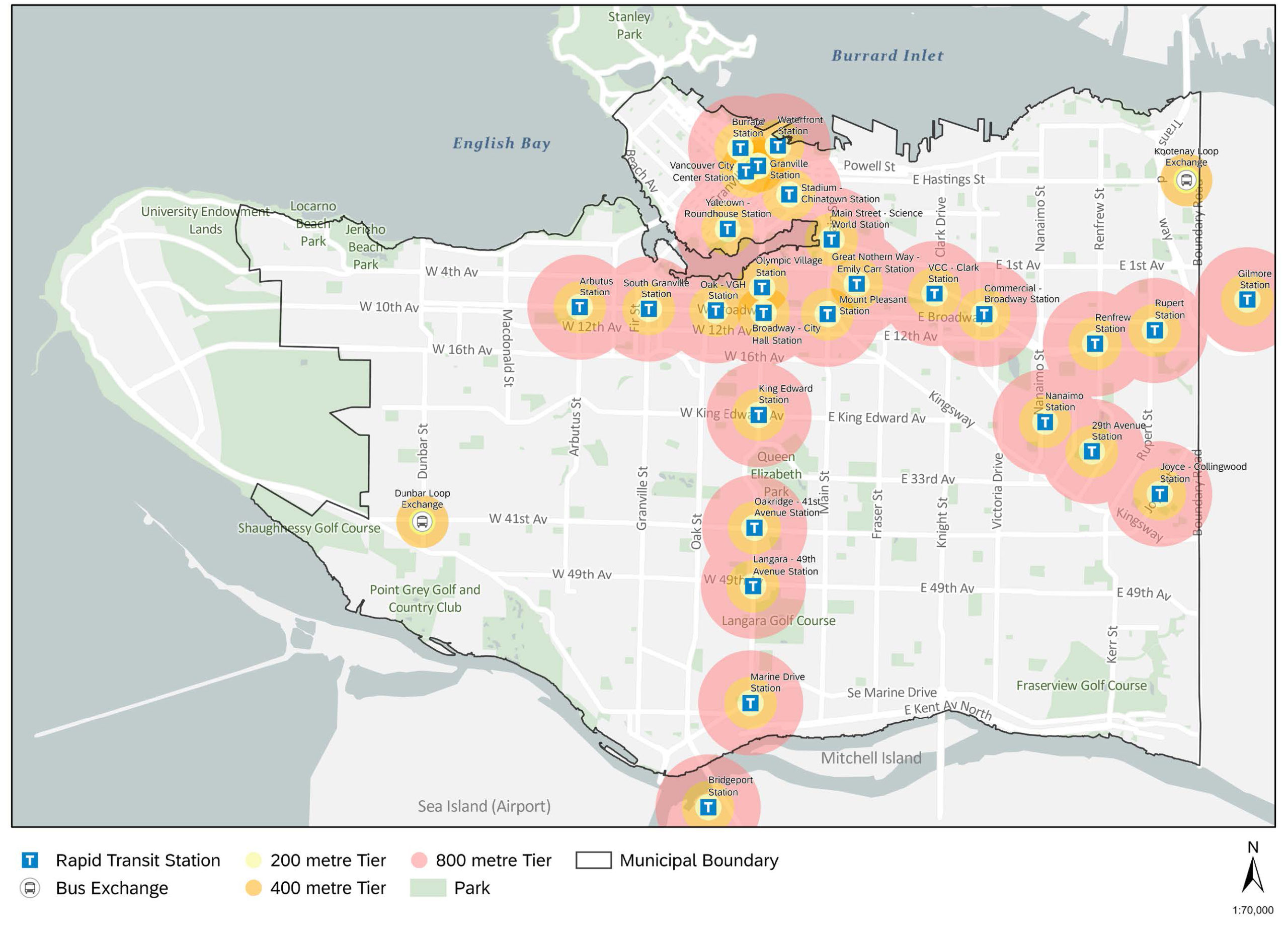

At the municipal and provincial levels, on April 23, City of Vancouver staff provided an update on their response to the B.C. NDP’s Bills 44, 46 and 47. Details were thin – the City is promising specific guidelines will follow in June – but there were notable points in the staff presentation and the accompanying report providing clues to what we can expect to see next month.

First, Bill 47, introducing the Provincial Transit-Oriented Areas (TOA), will have minimal effect in areas covered by existing high-density community plans, such as the Broadway Plan and parts of the Cambie Corridor. It is, perhaps, obvious that there is no potential upside in areas that already permit the provincial government’s new height and density minimums. But the City confirmed there would also be no change to development obstacles such as the two-tower-per-block rule or minimum-frontage restrictions. The provincial legislation prohibits municipalities from rejecting an application based on height or density alone, but allows for rejection on other municipal criteria.

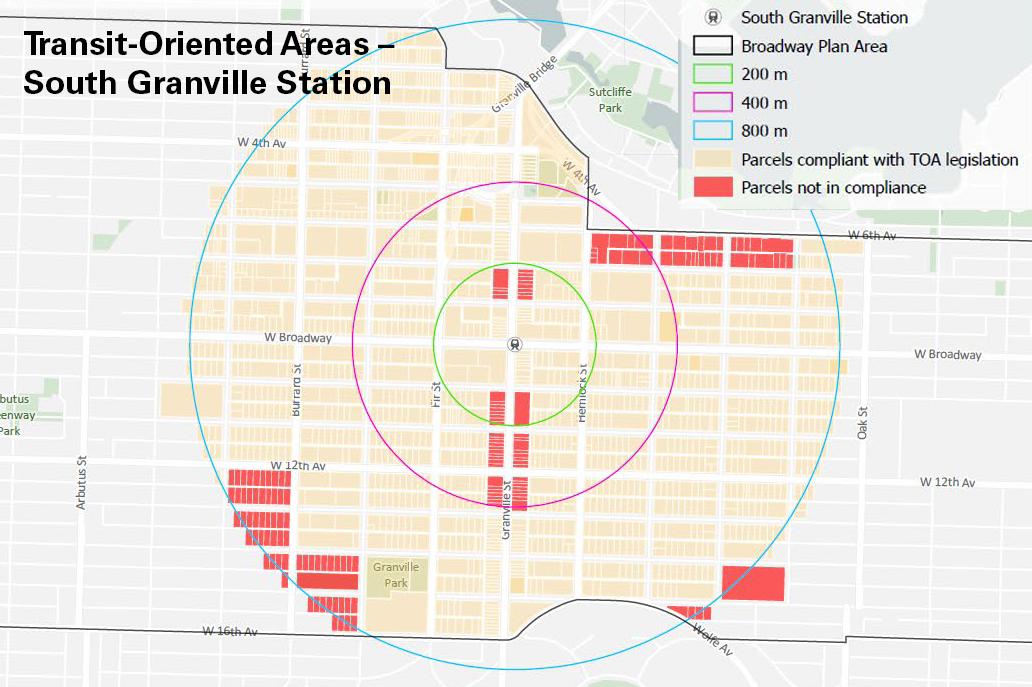

As 82% of the Broadway Plan area already meets or exceeds provincial TOA guidelines, at least on paper, only a few properties on the fringes are likely to see changes. As an example, a map of the South Granville Station area was presented showing a few minor changes required to align with TOA requirements (see slide below).

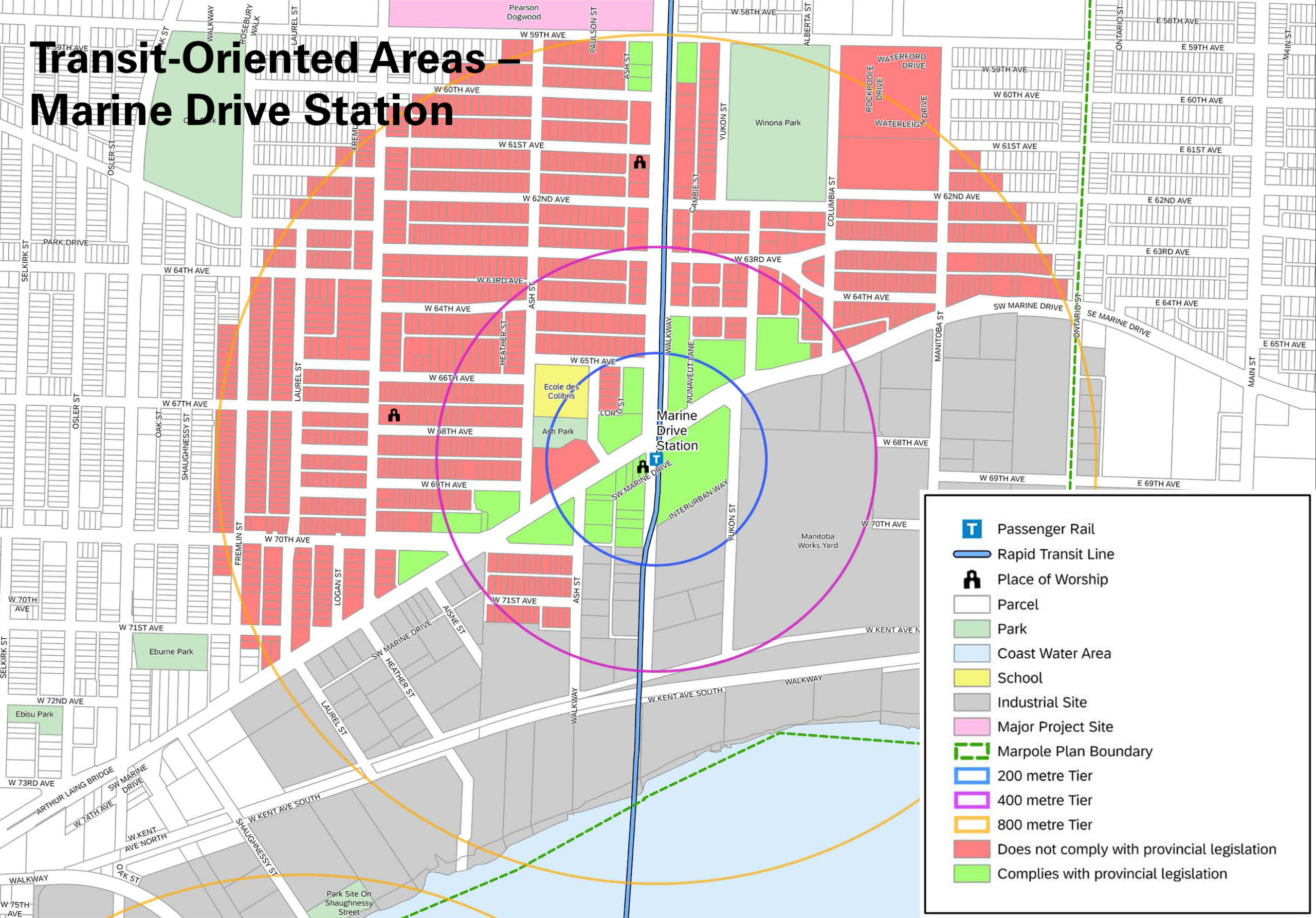

More change is anticipated in other parts of the city, such as in the Cambie Corridor near the Marine Drive Station, where the majority of residentially zoned parcels do not comply with the TOA guidelines. Similarly, some areas around other Vancouver transit stations have no community plan at all and will require wholesale changes to the current land use policies. Based on the discussion and responses to questions from Council, these areas are likely to see policies largely in line with recent community plans, with the Broadway Plan being the usual example. We anticipate that TOA policies will strongly favour rental tenure, with below-market housing requirements and built-form guidelines (i.e. minimum frontage requirements, maximum towers per block, strong tenant protections) designed to slow the pace of development.

Higher fees, but no more public hearings (eventually)

On another issue, the report to council suggests that developers should brace for increases to Development Cost Levies (DCLs). Given that Bill 46 expands the eligible DCL categories, the City of Vancouver signalled they are in discussions with the Province to remove or increase the current DCL cap of 10% of the value of a project. A new Amenity Cost Charge (ACC) policy framework is also expected by 2026, with Community Amentiy Contributions (CACs) to continue to apply in the interim. Language in the presentation suggests CACs could remain even after the new ACC is introduced to pay for any infrastructure not funded by DCLs and/or ACCs. Rather than streamlining the process and ensuring new supply is viable, the new development financing legislation appears to be adding more layers and expanding their reach, so that new developments will be expected to fund an even larger share of city services.

On the goal of speeding up the delivery of new housing, Bill 44 prohibits public hearings on rezonings that align with a municipality’s Official Community Plan (OCP). But the restriction does not apply in Vancouver. Unlike other municipalities, Vancouver has no city-wide land-use plan (called an Official Development Plan or ODP in Vancouver). In fact, most of the recent community plans are not considered ODPs, either, and therefore will continue to require public hearings for each new rezoning proposal.

On April 8, the Province introduced Bill 18 to rectify this omission, proposing changes to the Vancouver Charter that require the creation of a city-wide ODP and the elimination of public hearings for ODP-compliant rezonings. But this is Vancouver: a city-wide ODP is not expected to be completed until mid-2026. Until then, each and every rezoning in the Broadway Plan, Cambie Corridor Plan, and new TOAs will continue to be subjected to a full and lengthy public hearing process.