Want More Affordable Housing In Canada? Build More Houses

By Peter Shawn Taylor, Goodman Report

This article originally appeared in C2C Journal and is reprinted by permission.

C2Cjournal.ca | Ideas That Lead

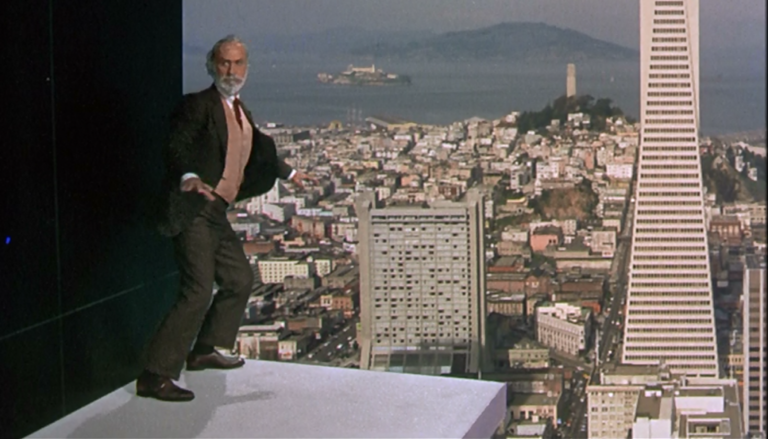

Canada’s housing market has an Alonzo Hawk problem. Alonzo Hawk was a stock villain played by veteran actor Keenan Wynn in several Disney movies of the 1960s and 1970s, including The Absent-Minded Professor and Son of Flubber. In Herbie Rides Again he was the conniving proprietor of Alonzo A. Hawk Wrecking & Building Corporation, intent on tearing down an old firehouse where a certain Volkswagen Beetle lived with its elderly owner. “His skyscrapers cast a cold and grey shadow over the children’s playgrounds all day long,” sneered one character. He’s “despicable, greedy, grumpy and wholly without principle or pity,” said another.

Watching Herbie Rides Again at a drive-in back in 1974 marked the first time your correspondent had ever encountered the occupation of land developer. And it seemed obvious to this nine-year-old moviegoer that they were on par with Nazis, bank robbers and dog-nappers in terms of routine villainy. Whatever land developers were up to – tearing down quaint old buildings to put up soulless new ones, or ripping up bucolic farmland – was evil simply by definition. It wasn’t until much later I considered how unfair it was to caricature the supply side of the housing market in this way.

Unfortunately, governments that ought to know better still cling to an Alonzo Hawk view of land developers and their trade. And it’s making life very difficult for Canadian families.

Amid the current and more pressing COVID-19 crisis, Canada is also widely considered to be experiencing a housing crisis. Earlier this year Ottawa City Council declared an “affordable housing and homelessness emergency” due to rapidly rising housing prices. Vancouver has done likewise. According to RBC Economics, housing affordability in Vancouver and Toronto “remains at crisis levels.” The share of average household income required to buy a home in Vancouver is an untenable 84.7 percent. In Toronto, it’s a still-crippling 66 percent. Rents in these markets, meanwhile, are also escalating.

“Every component of housing supply – materials, labour, financing, architectural expertise − is responsive to demand,” observes researcher Frank Clayton. “If prices go up, the market supplies more. Except for one thing: serviced land.” Unlike all the other factors of housing production, the supply of land is directly controlled by municipal and provincial bureaucracies.

Popular culprits include rapacious landlords, foreign buyers, money launderers, the “commodification” of real estate, easy credit and assorted “demand-side” factors. And much of the government policy response is contradictory. After having imposed a mortgage stress test to quell housing demand among eager new buyers, for example, the Trudeau Liberals last year introduced their First-Time Home Buyer Incentive that sees Ottawa directly encouraging newcomers to get into the market. Equally popular with municipalities and provinces are policies that attempt to defend homeowners and tenants from land developers and landlords, including rent control, zoning restrictions, tenancy protection and new taxes such as B.C.’s speculation and vacancy tax.

Largely missing from this crisis-mongering is recognition of the equally crucial supply side of the housing equation. Outside of eliminating immigration and population growth, there’s only one way to solve a housing affordability crisis: by building more houses. A lot more houses. If we really want to end Canada’s alleged housing emergency, we need to come to terms with our Alonzo Hawk problem and start treating developers, landlords and other housing suppliers as the solution rather than the problem.

Every housing market is influenced by a host of local factors, yet no market can avoid the iron law of supply and demand. Frank Clayton is a senior research fellow at the Centre for Urban Research and Land Development at Ryerson University in Toronto, and a long-time observer of the housing market in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) of southern Ontario. Clayton’s research points to underlying demand of more than 50,000 new housing units per year across the GTHA, due to strong long-term in-migration. Unfortunately, new supply over the past five years has averaged only 42,000 units. This unmet gap inevitably pushes up prices and, according to Clayton’s work, they’re rising faster than incomes. Hence affordability falls.

What’s behind this imbalance? A disturbance of basic economics. “Every component of housing supply – materials, labour, financing, architectural expertise − is responsive to demand,” Clayton observes in an interview. “If prices go up, the market supplies more. Except for one thing: serviced land.” Unlike all the other factors of housing production, the supply of land is directly controlled by municipal and provincial bureaucracies. And whether the land in question is greenfield plots on the outskirts of cities or redevelopment lots within city boundaries, the supply chronically lags far behind the amount that could be sold and developed were it available. Put simply, says Clayton, “There’s not enough land, and it takes too long to get it through the system.”

The GTHA is blessed with plenty of available land on its periphery suitable for new housing. But, says Clayton, “these days no one wants to expand to greenfield developments because it conflicts with all sorts of environmental concerns,” especially regarding suburban sprawl. This limitation has spilled over into the urban rental market. As single-family homes become increasingly dear, aspiring homeowners are forced to stay put. This in turn prevents lower-income families (nearly all of whom are renters) from trading up to bigger rental units. And so rents rise in tandem with house prices.

Making matters worse, the vast majority of developed land within Toronto’s city limits is zoned exclusively for single-family homes, making it all-but impossible to tear down existing houses and put up three or four-storey walk-ups to take the pressure off rents. Efforts to insert higher-density developments into these areas are habitually met with outrage from existing homeowners intent on preserving their neighbourhood as-is. Thus, despite rising prices, the market is incapable of meeting the new demand because the supply of land isn’t responsive to price.

Remove artificial blockages, Clayton notes, and housing crises tend to solve themselves over time. “Just loosen the land supply, and the private sector will do its job,” he promises. For proof, consider a recent report from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. (CMHC) examining the “elasticity of supply” of the Canadian housing market. In this context, elasticity of supply is the extent to which an increase in housing prices prompts an increase in the supply of new houses for sale. Edmonton and Montreal stood out in this cross-Canada comparison of major cities for their high elasticity. These two cities produced twice as many new homes for a given price rise as did Toronto and Vancouver.

Such market responsiveness has an appreciable impact on affordability. Edmonton, for example, has an RBC housing affordability index of slightly under 40 percent – less than half Vancouver’s ruinous 85 percent. Sprawling Calgary, which recently attempted to curb its suburban growth in favour of more downtown density, is midway between low-elasticity Vancouver and Toronto and high-elasticity Edmonton and Montreal. As the CMHC observes, policy-induced supply constraints create expectations among homebuyers that prices will continue to rise in the future, feeding further declines in affordability. There is only one solution. “Cities that keep expanding their boundaries are able to keep prices down,” observes Clayton, because developers can keep building new houses.

Further evidence of the effect of government regulations on housing affordability lies in New Zealand research showing 56 percent of the cost of a new house in urban, highly regulated Auckland (population 1.6 million) is due to land use restrictions and other rules that add costs, limit supply or otherwise frustrate the market. In the country’s less regulated housing markets, such as Palmerston North (population 86,000), such rules account for only 15 percent of total housing cost.

“When we talk about a housing affordability crunch we need to quantify the degree to which government land use regulations affect housing prices,” Clayton says. He adds that, “Ontario and B.C. are the two worst provinces for a planning system that does not respond to prices and fails to provide the necessary supply of serviced land.” At some point, the land supply issue will need to be resolved, because the fact remains that the large majority of Canadians – including immigrant families – don’t wish to dwell in apartments forever.

In Vancouver, where Canada’s housing crisis is most acute, the housing market admittedly faces more serious geographical constraints than Toronto. Here, redevelopment of existing developed land offers the most obvious way to deliver more supply. (Although the Agricultural Land Reserve across the Lower Mainland could offer plenty of land for housing if there was the political will to build on it.) Yet again, government policies purposely frustrate the supply of more housing, particular in the rental apartment category.

With 18 years in the commercial real estate business and over $3 billion worth of apartment buildings and other rental properties sold over his career, Mark Goodman has an unimpeachable perspective on the issue. “We see Economics 101 all the time, every day,” says Goodman, a principal in Goodman Commercial Inc. and publisher of the popular Goodman Report on Vancouver’s commercial real estate industry. “I’m sitting down with developers running the numbers, and more and more developers are simply walking away from Vancouver because the [financial] numbers don’t work.”

Major complaints Goodman hears from clients concern rent control, rental-only zoning rules, hefty taxes as well as permitting and consultation processes that routinely take up to four years, only to have entire projects dashed by a council vote at the final stage. “We know supply-side measures work,” he says. “But no one is doing enough to encourage [them].” Instead, many municipal politicians focus their efforts on ensuring the supply of housing in Vancouver never changes.

“Seattle doesn’t have rent control, they don’t have rent-only zoning, they aren’t dictating suite size or taxing their industry to death,” Goodman notes. Two years ago, Seattle’s providers built over 17,000 rental units; Vancouver added fewer than 2,000. Last year, average rental costs actually dropped in Seattle due to excess supply.

Most of Vancouver’s major apartment buildings are at least 50 years old, predating the condo boom that began in the 1980s. During the boom’s early years, many apartment buildings were torn down to make way for new condos. In response to complaints from displaced tenants, Vancouver City Council established a policy requiring a one-to-one replacement of demolished rental units in certain parts of the city. This policy − still in effect – has become a de facto moratorium on redeveloping land in some of Vancouver’s most desirable residential areas, by taking away landowners’ discretion to put properties to their most effective and rewarding use. “It is politically expedient to protect existing tenants by preventing the demolition of existing buildings, but this is making the problem worse,” says Goodman. So Vancouver’s rental stock simply sits and rots while developers look elsewhere for better opportunities.

The city claims to be addressing its rental apartment supply problem by allowing modest density increases in certain areas. Yet a suite of remaining policies still discourage new supply. For evidence of how a developer-friendly environment can solve such problems, Goodman points to Seattle, Washington, just a three-hour drive away. “Seattle doesn’t have rent control, they don’t have rent-only zoning, they aren’t dictating suite size or taxing their industry to death,” he notes. Two years ago, Seattle’s providers built over 17,000 rental units; Vancouver added fewer than 2,000. Last year, average rental costs actually dropped in Seattle due to excess supply; landlords have even been known to tempt new tenants with sweeteners such as two months’ free rent.

Vancouver could add a lot more housing – but doing so would require slashing government regulation. Consider the Senakw project in the Kitsilano neighbourhood on Squamish First Nation land. Freed from labyrinthine city controls due to its Indigenous status, Senakw will inject 6,000 new housing units, 70 percent of which are planned as rentals, across 11 buildings, providing a massive dose of density when and where it’s most needed. As for political approvals, a simple majority vote of Squamish First Nation’s 827 members last December did the trick. Construction is to start next year. “The fact this project was approved in months, rather than years, shows what’s possible when the city gets out of the way and we can simply concentrate on building a lot of new supply,” marvels Cynthia Jagger, a partner in Goodman Commercial.

Kitchener, in southwestern Ontario, similarly complains of an affordability crisis, with housing prices up by 88 percent and rents up by 35 percent over the past decade. “The solution is always more supply,” offers Andrew Macallum, president of the Waterloo Region Apartment Management Association, which represents 300 property owners.

Yet Macallum notes that most of what passes for local housing policy seems designed to forestall more rental housing, including regional apartment property tax rates that are double what homeowners pay, as well as rental unit licensing requirements and often conflicting municipal and provincial government regulations. “Over the years we have seen so many policies try to control the market that it has simply choked the ability of property owners to look after their own needs,” he says. Without a sufficient profit motive, Macallum adds, investors will inevitably look to put their money elsewhere.

Scratch a housing crisis and you will inevitably find government policies meant to protect existing homeowners and tenants at the expense of future supply. Zoning rules that forbid innovative or higher-density developments are the biggest obstacles to owner-occupied homes. Rent control is the most widely cited and pernicious issue when it comes to rentals. While average monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Waterloo Region is $1,045, Macallum reels off numerous local apartments where tenants are currently paying just $600 to $700 per month after being protected for many years by provincial rental control. “Why is that fair?” he asks. The owners of these properties are being robbed of the market rate for rent by government policy, which inevitably reduces their willingness to invest in additional rental housing.

A 2019 study in the American Economic Review repeats what is common knowledge among economists: “Rent control leads to a long-run decrease in the supply of rental housing.” While the Ford government in Ontario eliminated rent control for buildings constructed after November 2018, in Vancouver talk has recently shifted from rent controls, which limit rent increases during a given tenant’s tenure, to vacancy control, which imposes government-mandated limits on rent increases for the life of the apartment itself. If implemented, vacancy control would mean a conclusive end to any new construction in that city’s rental market.

A whole new vocabulary has been invented to heap scorn on landlords and land developers, including “renoviction” and “demoviction,” to delegitimize the process of renovating or demolishing apartment buildings to put up something newer and bigger. “These are slang terms that assume a greedy landlord is trying to toss helpless tenants out of their homes,” says Macallum dispiritedly.

Beyond the financial obstacles imposed on landlords and developers, the housing crisis is also bringing public opprobrium down on the market’s supply side. Someone has to take the blame for high prices. Owners who attempt to respond to market signals by upgrading decrepit rental buildings are a frequent target. Vancouver developer Jon Stovell of Reliance Properties was given the full Alonzo Hawk treatment in 2018 when he announced plans to redevelop a 60-year-old apartment building in Vancouver’s English Bay neighbourhood.

Despite lawfully exerting ownership rights over his own property, exceeding legal requirements for compensating existing tenants, and offering them right of first refusal on units when the building re-opens, Stovell was viciously attacked across social media. “Disgusting,” “SHAME”, and calls to “screw Stovell” were among the more polite responses. The project continues, despite the public outcry. “New investors are very hesitant to buy buildings in Vancouver that need a lot of work,” says Goodman, “because they know they’ll be vilified and victimized for ‘throwing people out on the streets’ when they are simply doing what needs to be done by upgrading the city’s housing stock.”

A whole new vocabulary has been invented that heaps scorn on landlords and land developers, including “renoviction” and “demoviction,” to delegitimize the process of renovating or demolishing apartment buildings to put up something newer and bigger. “These are slang terms that assume a greedy landlord is trying to toss helpless tenants out of their homes,” says Macallum dispiritedly. “But condemning landlords isn’t helping. We are part of the solution.”

Even the innovative Senakw project in Vancouver has been attacked by guardians of the status quo. “We’re talking about something that a lot of people detest, which is developers profiting,” Squamish councillor Khelselim, who goes by one name, told The Tyee. “But in this situation, it’s a community and a government making money to support themselves.”

The perception that market mechanisms are inappropriate or incapable of addressing the housing crisis is further exacerbated by the tendency of politicians in many cities to lump the disparate issues of homelessness and rising home prices into a single massive problem called the “housing affordability” crisis. While this bolsters claims that the housing market is failing on multiple fronts and requires even more government intervention, it is entirely unfair. Homelessness almost always involves addiction, mental illness and victimization, none of which can be blamed on housing suppliers. Finding a place for the homeless to live is separate from resolving blockages in the supply of new market housing.

As with the larger housing affordability problem, the social scorn heaped on developers and the supply side of the housing market is rooted in a basic ignorance of economics – as well as the envy and jealousy that are a large factor in urban politics. “There are plenty of people who will tell you developers are terrible people because they’re trying to make money,” observes Clayton. “There is a school of thought in urban planning circles and on city councils that considers housing a human right. But they simply don’t understand how a market works. People who invest in rental housing are providing a service, and that service is a place to live.”

Take away developers’ ability to make a profit, and they’ll take away the service. Anyone looking for an affordable place to live – and anyone in a position to influence urban housing policy – should keep that in mind.

If housing supply is a problem, making the suppliers of new housing out to be the villains of this movie is unlikely to provide a happy ending.

Peter Shawn Taylor is Senior Features Editor of C2C Journal and a freelance writer based in Waterloo, Ontario.